When you’re working with iron and iron alloys—especially in the form of steel— as many Xometry customers do, it’s helpful to know exactly what phases, or structures, they go through as they’re heated, cooled, and shaped and how those impact their strength, hardness, brittleness and overall useability. This is when you’d need a reference point, like the iron-carbon phase diagram, which we’ll look (and nerd out) at together in this article.

What Is the Iron-Carbon Phase Diagram?

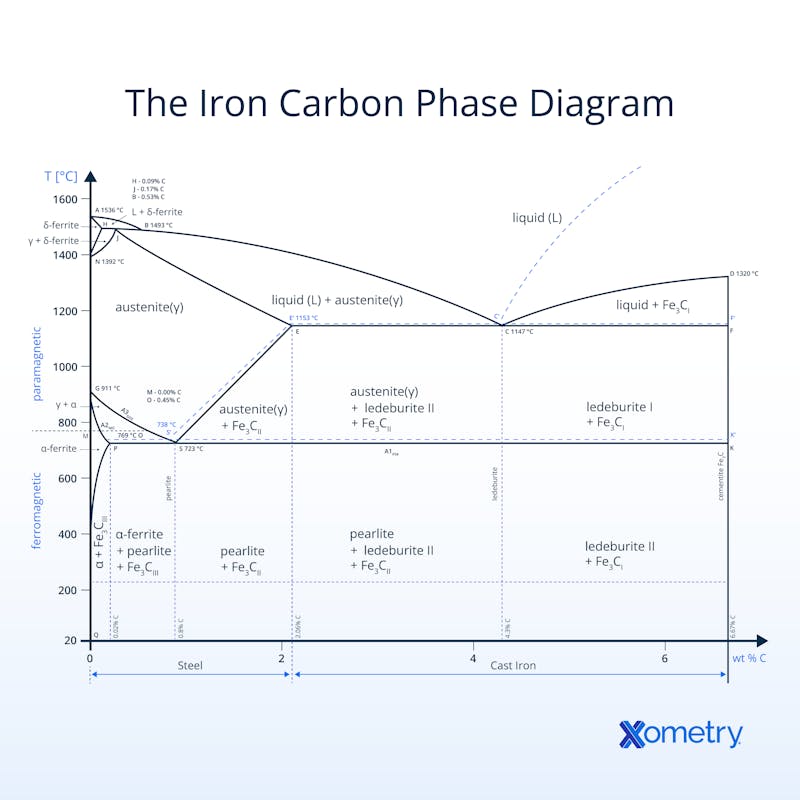

The iron-carbon phase diagram is simply a chart that shows the different structures (known as phases) of iron or steel as it goes through extremely hot or cold treatments. A scientist called Sir William Chandler Roberts-Austen created this guide in 1897 with information he pulled together using a device he invented that could measure the temperature of melted iron, and a microscope (an Adolf Martens, to be precise) that allowed him to see the metal’s grain structure. You may recognize the name because “austenite” was named after him. The diagram gives an idea of how different levels of carbon in the steel’s composition affect its changes and the chart features both paramagnetic and ferromagnetic steels. The best way to understand it, though, is to visualize the chart, which you can see illustrated below.

This diagram goes by several other names including the metastable iron-carbon, Fe-C, iron-iron carbide, and the Fe-Fe3C phase diagrams. All the names point to the iron-carbon relationship and how it handles different temperatures. It came to be with the help of several scientists’ work and the basis comes from a T-x diagram, which isn’t as comprehensive but was certainly the start of the full chart.

Having this visual helps metallurgists, engineers, and manufacturers understand changes in an iron alloy’s microstructure, temperature phases and composition shifts - this isimportant to know when it comes to choosing the right alloys. This accurate and researched-backed diagram will guide you on when to harden, cool and heat different alloys, but it draws the line at offering any information on surrounding iron-carbon phases, i.e., you won’t find the non-equilibrium martensite phase here. And, it also won’t tell you anything about heating and cooling rates for different steels and phases, or exact phase properties.

What Is the Other Term for Iron Carbon Phase Diagram?

There are several other names that might be used to refer to an iron-carbon phase diagram such as: metastable iron-carbon phase diagram, Fe-C phase diagram, iron-iron carbide phase diagram, and Fe-Fe3C phase diagram. A metastable iron-carbon phase diagram is used to emphasize the fact that the iron-carbon relationship is metastable due to the slow cooling rates of iron alloys. In the term “Fe-C phase diagram,” Fe-C is shorthand for iron-carbon. The diagram is also known as a “steel phase diagram” since iron alloys are steel. “Steel” is used in place of iron-carbon to show that the diagram is used to understand its microstructure. “Iron-iron carbide phase diagram” is used to represent the iron carbide part of the phase diagram. In the term “Fe-Fe3C phase diagram,” Fe-Fe3c is shorthand for iron-iron carbide.

What Is the Origin of the Iron Carbon Phase Diagram?

The iron-carbon phase diagram was developed to show the relationship between carbon content and temperature treatment. The diagram was not invented in one single instance but was the result of a series of works coming together to form what is now considered the iron-carbon phase diagram. In 1897, Sir William Chandler Roberts-Austen used information gathered by an Adolf Martens microscope, which could study the grain structure of the metal and data from a device he invented to measure the temperature of melted iron to plot a T-x diagram. The T-x diagram isn't a true iron-carbon diagram because it is not in equilibrium. However, it is considered to be the basis of an iron-carbon diagram.

How Does a Iron Carbon Phase Diagram Work?

If you look at the chart, you’ll see the temperature and the carbon content (as a percentage of weight) are plotted on the Y and X axes respectively. There are also segments that horizontally span the graph, which represent a different phase in the changing of the iron-carbon microstructure. There are also temperatures like 723℃, which is considered the critical or A1 temperature, meaning that any austenite in iron will turn into the eutectoid pearlite and double how much ferrite is in its structure. The chart also shows how two iron-carbon alloys can have the same chemical composition, they won’t necessarily have the same microstructure.They’ll be in varying phases at different temperatures.

Heat treatment is used to change the iron-carbon alloy’s microstructure, which is another reason you’ll need this diagram. If, say, you’re cooling pearlite at a rate of 200 ℃ per minute, the hardness you’ll be able to achieve is 300 DPH. If you up the temperature to 400 ℃ per minute for cooling, then you can increase the hardness to 400 DPH. This happens because carbon doesn’t get as much time to move through the lattice structure of pearlite. If you take it a step further and liquid quench the pearlite at 1,000 ℃, carbon can’t move at all and you can achieve the hardest and most brittle martensite structure.

What Is the Importance of the Iron Carbon Phase Diagram?

The iron-carbon phase diagram is an important tool used to understand the microstructure of iron-carbon alloys. It is important to use a graph to demonstrate how the function of temperature and carbon content affect iron-carbon alloys, as without this it would be hard to communicate at what temperature and carbon content austenite becomes austenite + cementite (for example).

What Are the Different Structures in the Iron Carbon Phase Diagram?

Each phase’s atoms are arranged in a different way, and this arrangement is called the crystal structure. The properties, like strength or flexibility, will all depend on which structure category the phase falls into. Here’s a brief explanation of the five most common crystal structure types:

Body-centered cubic (BCC) crystal: This structure is like a cube with an atom in each corner and one slap bang in the middle. It’s strong but not very flexible, so materials with this type (like ferrite) tend to break easily, even though they’re most times hard.

Body-centered tetragonal (BCT): This is very similar to BCC, the only difference being that it’s stretched in only one direction—something that makes it very strong and hard. Not that you’ll be surprised, but martensite has a BCT structure.

Face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal: Just like with BCC, with FCC there is an atom at each corner of the cube, but this one has an extra one in the middle of each of the cube’s faces. Materials that fall into this category (like austenite) are flexible and ductile.

Lamellar: Materials that have this structure have thin alternating layers made from two materials: soft and ductile ferrite, and hard but brittle cementite.

Orthorhombic: This is a rigid and hard structure that we can describe kind of like a stretched cube with sides of all different lengths. Cementite is orthorhombic, which is why it’s both tough and brittle.

What Are the Different Phases in the Iron Carbon Phase Diagram?

The phases you’ll find expressed on the iron-carbon diagram are explained below.

The different phases in the iron carbon phase diagram are listed and discussed below:

1. δ-ferrite

ẟ-ferrite is a low-carbon (almost pure iron) phase that has a body-centered cubic crystal structure. With an increase in carbon content, cementite will begin to form creating ferrite + cementite. δ-ferrite is stable up to 912 ºC. Above 912 ºC, δ-ferrite transforms into a face-centered cubic austenite. δ-ferrite is very magnetic and ductile but has a low strength.

2. γ-austenite

y-austenite is a solid face-centered cubic phase, which is stable up until 1,395 ºC, at which point it transforms into a body-centered cubic ferrite. Most iron alloys that receive heat treatment start in the γ-austenite phase. y-austenite is non-magnetic, soft, and ductile.

3. α-ferrite

α-ferrite is a high-temperature iron-carbon phase that is created by cooling a low-carbon concentration in the liquid state. The liquid state is then cooled to an austenite phase. The presence of α-ferrite in iron-carbon resists lattice dislocation and therefore slows grain growth, reduces vulnerability to fatigue, and increases strength.

4. Fe3C (Cementite)

Fe3C is the chemical name for cementite, also known as iron carbide, which starts to be present at any carbon content above zero, but no iron is fully cementite until it includes 7% carbon content. Cementite can be produced through the cooling of austenite or the tempering of martensite. Cementite is hard, but also brittle, but cementite’s best property is its corrosion resistance which can be achieved when dipping cementite in a solution of 1–3% sodium chloride.

5. Ledeburite

Ledeburite is a mix of austenite and cementite and has a carbon content of 4.3% carbon. The carbon content of ledeburite is too high to be found in steel but is found in cast iron. Ledeburite has a melting point of 1,147 ºC.

6. Pearlite

Pearlite is formed when an austenitic phase of an iron-carbon alloy is cooled slowly. Pearlite is formed of alternating layers of ferrite and cementite, which gives pearlite significant toughness and strength.

7. Martensite

Martensite is created by rapidly cooling a face-centered cubic austenite phase. This process is referred to as a martensitic transformation. The martensitic transformation creates great hardness and strength. Quenching is used to invoke a martensitic transformation.

What Is the Purpose of Heat Treatment in the Context of the Iron-Carbon Phase Diagram?

The purpose of heat-treating iron-carbon alloys is to change the microstructure of the alloy and therefore its properties. By changing the rate of cooling, the properties of an iron alloy can be altered. When cooling pearlite at a rate of 200 ºC per minute, a hardness of 300 DPH can be achieved. Cooling at 400 ºC can achieve a hardness of 400 DPH. The reason there is an increase in hardness is due to the formation of fine pearlite and ferrite microstructure in the pearlite. This is because carbon has less time to move through the lattice structure of the pearlite as it cools. Therefore, when cooling, using liquid quenching at 1,000 ºC, the carbon has no time to move. This forms a martensitic microstructure that has a hardness of 1,000 DPH. Martensite has the hardest and most brittle microstructure of all iron alloys, but after tempering by holding martensite at 400 ºC it becomes less hard and brittle.

What Is the Most Important Temperature in the Iron-Carbon Phase Diagram?

There are many important temperatures in the iron-carbon phase diagram. One of the most important is 723 ºC, which is known as the critical or A1 temperature. It is the point at which any austenite in iron, cast iron, or an iron alloy transforms into the eutectoid pearlite. At this point, the microstructure has double the amount of ferrite as it does pearlite.

What Are the Different Reactions in the Iron-Carbon Phase Diagram?

There are two factors that have the biggest impact on determining what phase iron-carbon alloys are in—temperature and carbon content. This happens through different types of bonding, which we’ll describe below.

Eutectoid

This happens when one solid phase separates out into two solid phases after cooling, and is known as the “eutectoid point” (you can see this on the diagram at 0.8%wt and 723 ℃). This point is where austenite turns into ferrite and cementite, too.

Eutectic

Similarly, this one also transforms into two solids—but from a liquid, and at the melting point, hardening as it cools.

Peritectic

Though it’s rare to see, this reaction happens when a molten and solid phase forms a second solid phase.

How Can the Iron-Carbon Phase Diagram Help Engineers and Metallurgists?

The iron-carbon phase diagram can be used to predict the phase states within the material if the heat treatment it has received and the chemical composition is known. Since the physical properties of an iron-carbon alloy depend on the phases of the iron-carbon alloy, the iron-carbon phase diagram can aid engineers and metallurgists in predicting the properties and behavior of such an alloy. For example, if an iron-carbon alloy of 0.8% carbon is heated above 723 ºC and then liquid quenched, then it is known that martensite is formed and the iron-carbon alloy will be hard but brittle.

How Does the Quenching Rate Affect Steel Alloy Microstructure?

The aim of quenching is to alter the microstructure of iron-carbon alloys to increase their hardness. This works because when iron carbon is heated above a certain temperature, it transforms into an austenite phase which has a face-centered cubic structure, which can easily dissolve carbon atoms. Iron carbon which cools slowly at 400 °C per minute, for example, allows the dissolved carbon atoms to be released from the lattice structure. However, when austenite is quenched, at 1,000 ºC per minute, the carbon becomes trapped in the lattice. This increases the metal's internal stresses and makes the metal hard and brittle.

How Does the Iron-Carbon Phase Diagram Help Predict the Mechanical Properties?

The iron-carbon phase diagram maps out all of the possible temperature treatments and carbon contents an iron-carbon alloy can experience. If the temperature and carbon content of an iron alloy are known, then the iron-carbon phase diagram can be used to predict in which phase states the iron-carbon alloy now exists. Iron-carbon alloys are well known and tested, so if the phase state of the iron is known, the mechanical properties can be predicted from known data. For example, martensite is known for being the hardest and most brittle steel. It can be predicted that if steel has been heated to above 723 °C and then quenched, it will exist in a martensitic state.

What Are the Types of Steel Used in the Iron Phase Carbon Diagram?

High, medium, and low carbon steels are the types of steel that can be referenced on the iron-carbon phase diagram—we’ve put a little bit about each below.

1. High-Carbon Steel

High-carbon steel, also known as carbon tool steel, has a carbon content of 0.60–1.50%. The high carbon content means it is harder and stronger than lower-carbon steels but it is also less ductile. High-carbon steel is also more corrosion-resistant than lower-carbon steel, if there is no addition of other alloying elements, such as chromium which can affect the corrosion resistance of steel. High-carbon steel is used in cutting tools, dies, springs, and high-strength wire.

2. Medium-Carbon-Steel

Medium-carbon steel has a carbon content of between 0.30–0.60%. Medium-carbon steel is the range that has the best balance between the properties of low- and high-carbon steel. Although medium-carbon steel is harder and stronger than its low-carbon counterparts, it often requires quenching to achieve the desired hardness. Medium-carbon steels are commonly used in: pressure vessels, gears, shafts, axles, and machinery parts.

3. Low-Carbon Steel (or Mild Steel)

Low-carbon steel has a carbon content between 0.05–0.30%. Low-carbon steels are known for their ductility and malleability. Due to the small amount of alloying carbon, low-carbon steel is the cheapest and most widely used as a general-purpose steel. Low-carbon steel is used for: fasteners, building frames, bridges, body panels, and pipework.

What Are the Advantages of the Iron-Carbon Phase Diagram?

Iron carbon diagrams are in widespread use due to their advantages which include:

- It is relatively easy to interpret.

- It can display information on a large number of phases.

- It is accurate.

- The information is well supported by research.

What Are the Disadvantages of the Iron Carbon Phase Diagram?

There are also disadvantages to the iron-carbon phase diagram which are:

- The diagram does not include all information, such as the non-equilibrium martensite phase.

- There is no time indication for rates of heating and or cooling.

- There is no indication of the exact properties of the different phases.

Is the Iron Carbon Phase Diagram Accurate?

Yes, generally iron-carbon phase diagrams are accurate. However, the accuracy of the diagram will vary depending on the origin of each diagram. There are some limitations of the diagram, such as the omission of bainite and martensite metastable phases. It also does not give time-dependent information on the formation of pearlite, bainite, or spheroidite.

How Xometry Can Help

We have a lot of experience working with iron and steel here at Xometry, and we have numerous services that fall under this material category. You can get free, instant quotes on our website for processes such as metal 3D printing, sheet metal fabrication, sheet cutting, and tube bending.

Disclaimer

The content appearing on this webpage is for informational purposes only. Xometry makes no representation or warranty of any kind, be it expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or validity of the information. Any performance parameters, geometric tolerances, specific design features, quality and types of materials, or processes should not be inferred to represent what will be delivered by third-party suppliers or manufacturers through Xometry’s network. Buyers seeking quotes for parts are responsible for defining the specific requirements for those parts. Please refer to our terms and conditions for more information.