You’re no doubt familiar with the term alloy, but maybe not some of the intricacies of their characteristics. We rarely use pure metals, other than in decorative or catalytic applications - they’re just not very strong compared to alloys.

Alloys are metals made up of two or more elemental metallic constituents, often with non-metal additions. The addition of various elements to a pure metal’s lattice structure enables metals to have properties that they do not have in their pure forms. Typically, alloys are stronger, harder, more durable and in many cases, more corrosion-resistant than their pure metal counterparts.

Alloys have a lot of different compositions. You see properties of some of the modifying additions ‘adopted’ by the mixture. The primary element in the alloy is typically a material that can accept dissolution of other metals to a degree, to avoid regionalization and disuniformity.

Examples of alloys include steel, brass and aluminum alloys, such as aluminum 6061, which is one of the most common alloys used by Xometry customers for CNC machined parts. Alloys are used in a wide range of applications, from infrastructure and vehicles to consumer goods and medical equipment. In this article, we will explain what an alloy is and review the different types, compositions, and applications of alloys.

What Is an Alloy?

An alloy is a material composed of a metallic base, usually the large majority component, and additional metal or non-metal components that are added as property modifiers. Alloys are manufactured and carefully tuned by experiment to deliver desirable properties that are not present in the primary material.

Many alloys are made purely of metals, but non-metal additions such as Silicon, Sulfur, Carbon, Nitrogen, and other light elements are commonly used as property adjusters.

What Is the History Alloys?

Alloys have been used since as early as 3000 BCE. The first known alloys were brass (Copper and Zinc) and bronze (Copper and Tin). Both of these likely originated from early metallurgical learning, where two ores of different compositions were smelted together. We will never know if the first alloys were the result of brilliance or mistake, but what followed is the entire history of metallurgy and our technological society.

Notably, the element Nickel was not isolated until the 19th Century, but its presence was felt in some Copper deposits, which, when smelted, formed cupro-nickel. These ores were often described as ‘having the devil in them’ as the Nickel content made the Copper very hard to work. Nick is an old word for the devil.

Brass and the much more serviceable bronze both alter the soft and ductile nature of Copper to deliver harder, tougher, and more resilient materials - and in the case of bronze, the ability to hold an edge. Bronze was the first weapons-grade metal, and it destroyed empires. The best bronze in ancient Europe came from Cyprus, and the Mycenaeans, Greeks, and Romans built their empires on it. Today, brass and bronze are still frequently used to create parts and components; you can find them as auto-quotable options within Xometry’s instant quoting engine.

In about 1,600 BCE, wrought iron and cast iron began to be produced. Iron is much harder to extract from the ore, and it is unlikely that it was refined by accident. We have experimental metallurgists from 4,000 years ago to thank for it. Pure iron is soft, ductile and malleable and really not of much utility. The big step comes in smelting and working the Iron with a pretty high Carbon content, to alter its structure. The first Carbon is used as a reducing agent in the smelt, so it became an alloying agent by stealth. Cast and then hot-worked (wrought) Iron displaced bronze, and empires fell.

Iron and the alloy family then remained mostly unchanged for 3,000 years, other than a few highlights:

- Adding/controlling the Carbon content became an art form. Sword makers in Toledo (which is an awesome city in Spain with great views) and Jōmon period Japan (up to 1,000 BCE) both learned to make steel, either by adding Carbon by hand (Japan) or by using wooden anvils (Toledo).

- Later on, in various regions, a kind of case hardening by quenching in Nitrogen-rich water added an extra bite to the blade.

It really wasn’t until the Industrial Revolution in the 18-19th centuries that metallurgy became a formal science, delivering many of the alloys commonly used today. Advances in chemistry allowed the isolation of metallic elements such as Manganese, Nickel, and Chromium, Aluminum, Titanium, Magnesium and other elements used in alloys today. The Industrial Revolution is one of my favorite periods of history and continues to shape our lives today.

What Is the Other Term for Alloy?

A few other terms for “alloy” are: mixture, fusion, amalgam, solid solution, and admixture.

What Is an Alloy Made Of?

Alloys are merged materials composed of a primary base element combined with various secondary elements. The base element provides the fundamental structure and typically the solubility medium that disperses the other components uniformly, while the secondary elements are added in specific proportions to adjust and bequeath desirable properties of the final material. The resulting alloy inherits a summary of the characteristics of all its constituents and in many cases, unexpected cooperative gains that none of the individual constituents display, leading to selectively improved performance.

How Are Alloys Made?

Alloys are made by smelting and blending the base metal and additional elements (metals and/or non-metals) and allowing them to cool. The admixing is often performed in the melt, but many non-metallic additives can be worked in after initial solidification, by various methods. Two primary types of alloys are used; substitutional and interstitial alloys.

- In substitutional alloys, like brass and bronze, the atoms of all of the alloying elements are similar in size. The atoms of the alloying elements substitute for the same sites the atoms of the base material would occupy in its lattice structure. This lends distributed property adjustments to the lattice that are intrinsic to the metals involved. In most cases the substitution disrupts and stresses the lattice, reducing planar slip potential by blocking.

- In interstitial alloys such as steel, the atoms of the alloying elements (Carbon, Silicon, Nitrogen) are smaller and fit in between the atoms of the base metal. This placement also acts to disrupt slippage and fracture. However, some non-metallic elements such as Silicon act as crystal growth triggers, altering the typical crystal size to add strength and resilience as more and smaller crystals deliver a tougher material.

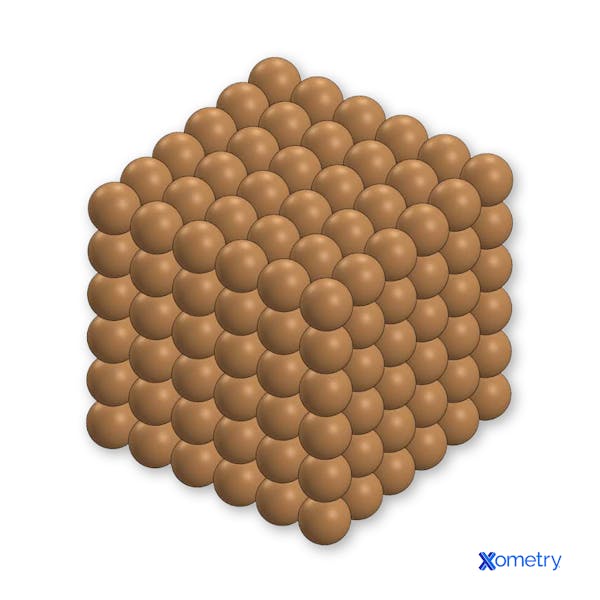

Figure 1: A representation of pure Copper microstructure, with soft and

easily movable slip planes.

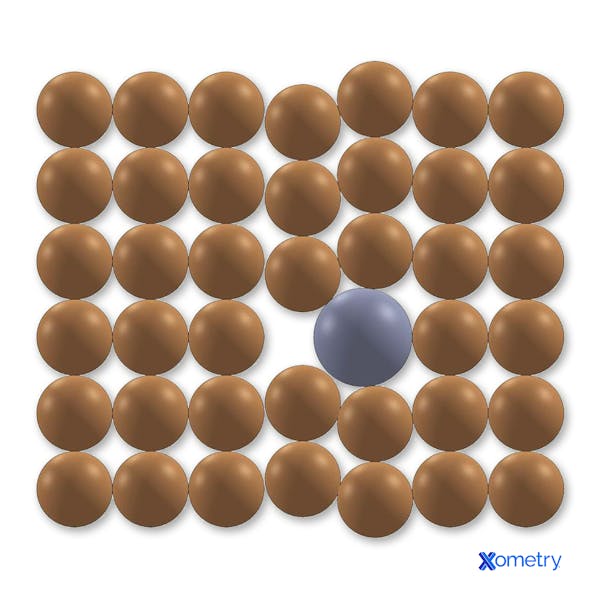

Figure 2: The slip plane disruption of a single Tin atom in Bronze, toughening the material by lattice strain and crack blocking as a substitutional alloy.

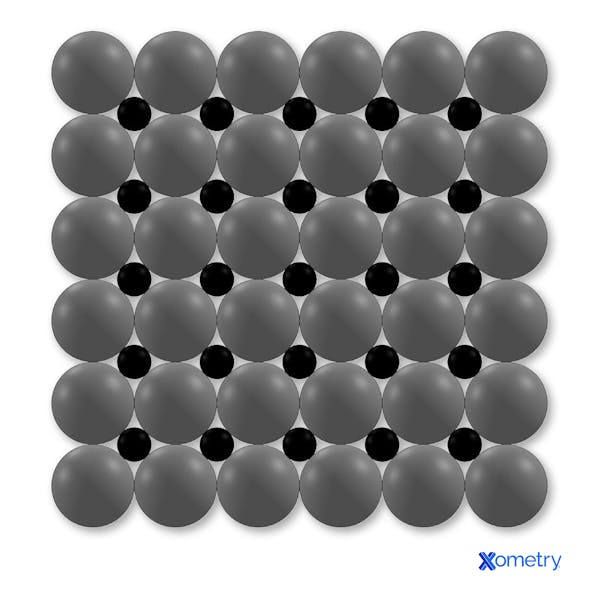

Figure 3: Carbon atoms in an iron lattice to make steel, an interstitial solid solution.

The carbon acts as slip plane barriers increasing toughness, hardness and reducing ductility.

What Are the Characteristics of Alloys?

From your own experience, you probably know that characteristics will vary widely between types of alloy, but in general, alloys have benefits like those below:

- Improved Properties: You can find alloys that have better properties than metals alone. Alloy materials aim to deliver improved properties, compared with the constituents. Steel is stronger and more durable than Iron alone, and bronze is harder and more corrosion-resistant than pure Copper.

- Customizability: Alloys enable desirable properties that do not exist in the original pure metals to be obtained. For instance, aluminum alloys are much stronger and harder compared to pure aluminum, which is soft and malleable.

- Diversity: Several hundred different alloys currently exist. Alloys have been created to serve many different applications. New alloys are also constantly being developed.

- Strength: Alloys are stronger than their pure metal counterparts, which can give you many benefits. Additional elements in the base metal’s lattice structure make it harder for atoms to move around, which makes the material stronger.

- Corrosion Resistance: Alloys are often of higher corrosion-resistance than their pure primary component. Additive elements are usually constituted to oxidize and form a barrier layer on the surface of the alloy. This is particularly the case with stainless steels, such as stainless steel 316/L, a common choice among Xometry users.

- Electrical Conductivity: Alloys tend to have lower electrical conductivity than pure metals. The addition of atoms with different charges in the lattice structure of the base metal can interfere with the flow of electrons through an alloy.

- Thermal Conductivity: Alloys tend to have lower thermal conductivity than pure metals. A metal’s ability to conduct heat is dependent on the number of free electrons within its atoms. The addition of atoms with different charges in the lattice structure of the base metal can interfere with the flow of electrons through an alloy.

What Is the Color of the Alloy and What Does an Alloy Look Like?

The colors of alloys vary based on their composition and base element.

Copper alloys, such as bronze, brass, etc., are typically shades of yellow, orange, and red, depending on their copper content. An exception is cupro-nickel, used for coins and decorative purposes, which is bright silver when polished.

Steel alloys are bright or dull silver in appearance - more lustrous than pure iron.

Gold is a commonly alloyed elemental metal. Pure gold is bright, lustrous, and yellow, but silver additions reduce the yellowness to a lighter shade, while copper additions redden the appearance.

Aluminum alloys are all bright silver when freshly cut and dull to a gray and matte appearance as they age/oxidize.

Choose From Dozens of Alloys for Your Custom Parts

What Are the Different Types of Alloy?

The most common classes of alloys that you are likely familiar with are described here:

1. Steel

You see it everywhere you look, from Superman to the supermarket. Steel is ubiquitous and key to most industries. They are based on elemental Iron with a small amount (<2%) of Carbon added. Other intentional alloying elements added to improve or alter the properties of steel include manganese, nickel, chromium, and vanadium. Many other elements may be added for specific purposes and or be present as residuals. Although properties vary based on chemical/metallurgical composition, pure iron is ductile, soft and malleable where steel is stronger, harder and tougher, but sacrifices ductility. Stainless steels are also corrosion-resistant because of their high Chromium, Nickel, and Manganese content. It is often used in buildings, ships and watercraft, automobiles, medical equipment, household appliances, and tools. For more information, see our guide on Steel Alloy.

2. Brass

Brass, as you may know, is an alloy composed of approximately 66.6% copper and 33.3% zinc. However, many brass alloys that vary on this basic formula have been developed. These may contain such additional alloying elements as aluminum, antimony, iron, or silicon. In general, brass is stronger, harder, less dense, and more easily machinable than pure copper. Brass is often used in buttons, hardware, ammunition cartridge cases, and marine applications.

3. Bronze

Bronze is an alloy composed of approximately 88% copper and 12% tin. Additional elements such as aluminum, phosphorus, manganese, and silicon are sometimes added. Compared to pure copper, bronze is stronger, harder, more corrosion-resistant, and easier to cast. You’ll often see Bronze used in sculptures, gears, bushings, and tools.

4. Aluminum Alloys

Aluminum alloys result from the combining of pure Aluminum with smaller amounts of Manganese, Copper, Magnesium, Silicon and Zinc. A bewildering array of Aluminum alloys are manufactured, often for narrowly specific applications. Aluminum alloys are stronger than the pure metal, to the point of strength to weight ratios higher than steel. They are harder, more durable and more corrosion resistant. Aluminum alloys are applied in a wide spectrum of applications including: cars/trucks/trains, aerospace, medical equipment, consumer products, high tension wiring and electronics. Aluminum 6061 is one of the most commoditized materials we offer due to its versatile nature, ease of use in manufacturing, recyclability, and low cost.

5. Titanium Alloys

Titanium alloys contain Titanium as the base metal and additions of Aluminum, Manganese, Zirconium, Chromium and Cobalt. While pure Titanium has an exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, its alloys are even stronger, more flexible, and more corrosion-resistant. They are increasingly used in aircraft and automotive components, marine applications, and medical devices and equipment for the weight benefit and corrosion resistance they deliver. Xometry offers autoquoting for machined parts made from Titanium Grade 2 and Grade 5, two popular titanium alloys.

6. Nickel Alloys

Nickel alloys contain other elements such as Iron, Chromium, and Copper. They are widely used in industrial and marine environments for their corrosion resilience in aggressive environments, and turbine/rocket components for their high temperature tolerance/strength. They can also possess desirable magnetic properties. You’ll find Nickel alloys are often used in electrical components and electronics.

7. Copper-Nickel Alloys

Copper-nickel (Cu-Ni) alloys are primarily composed of copper and nickel but sometimes include other elements such as silicon, iron, manganese, and zinc to obtain different properties. The properties obtained differ depending on the exact chemical composition of the Cu-Ni alloy. Generally, copper-nickel alloys are excellent electrical conductors, are corrosion resistant, and have high tensile strength (340-650 MPa). Cu-Ni alloys are commonly used in electronics, marine applications, and pipelines.

What Are the Properties of Alloys?

Properties of some of the more common types of alloys are shown in Table 1 below:

| Alloy Type | Composition | Properties | Common Uses | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Alloy Type Steel | Composition

| Properties Strong, hard, durable, malleable, machinable | Common Uses Construction, manufacturing, automotive, medical | Examples Structural components in buildings, automotive parts, medical instruments |

Alloy Type Brass | Composition

| Properties Durable, electrically conductive, corrosion resistant, machinable | Common Uses Apparel, hardware, ammunition, marine | Examples Zippers, bolts, fitting, jewelry, musical instruments |

Alloy Type Bronze | Composition

| Properties Strong, hard, corrosion resistant, machinable | Common Uses Artwork, gears, bushings, tools | Examples Sculptures, electrical connectors |

Alloy Type Aluminum Alloys | Composition

| Properties Light, strong, durable, corrosion resistant, machinable | Common Uses Frames for airplanes, automobiles, machinery, etc. | Examples Fuselage for airplanes, bicycle frame |

Alloy Type Titanium Alloys | Composition

| Properties Light, strong, hard, durable, corrosion resistant, biocompatible | Common Uses Medical implants, aircraft, automobiles | Examples Joint implants, airplane parts, automotive parts |

Alloy Type Nickel Alloys | Composition

| Properties Excellent electrical and thermal conductivity, corrosion resistant | Common Uses Electrical and electronic applications | Examples Electrical wiring, transformers, memory storage devices |

Alloy Type Copper-Nickel Alloys | Composition

| Properties Strong, corrosion resistant, ductile | Common Uses Marine applications, power generation, oil and gas piping systems | Examples Offshore oil and gas platforms, boat hulls |

| Alloy Type | Density (g/cm3) | Melting Point (°C) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Alloy Type Steel | Density (g/cm3) 7.80-8.00 | Melting Point (°C) 1300-1540 | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) 44.0-52.0 | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) 3-15 |

Alloy Type Brass | Density (g/cm3) 8.40-8.73 | Melting Point (°C) 900-930 | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) 111-120 | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) 28 |

Alloy Type Bronze | Density (g/cm3) 7.40-8.92 | Melting Point (°C) 950-1025 | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) 26-83 | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) 15 |

Alloy Type Aluminum Alloys | Density (g/cm3) 2.50-2.83 | Melting Point (°C) 463-1038 | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) 70-237 | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) 61 |

Alloy Type Titanium Alloys | Density (g/cm3) 4.42-4.84 | Melting Point (°C) 1538-1704 | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) 7.2-22.7 | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) 0.96-1.87 |

Alloy Type Nickel Alloys | Density (g/cm3) 8.09-8.91 | Melting Point (°C) 875-2732 | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) 8-17 | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) 1.35-20.28 |

Alloy Type Copper-Nickel Alloys | Density (g/cm3) 8.91-8.94 | Melting Point (°C) 1170-1240 | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) 25-40 | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) 3.45-9.07 |

Table Credit: https://www.copper.org/

| Alloy Type | Corrosion Resistance | Oxidation Resistance | Reactivity | Magnetic Properties | Flammability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Alloy Type Steel | Corrosion Resistance Susceptible to corrosion unless surface treated or stainless alloy | Oxidation Resistance Readily reacts with oxygen | Reactivity Reactive to acids and alkalis | Magnetic Properties Ferromagnetic (except austenitic stainless steels) | Flammability Non- flammable |

Alloy Type Brass | Corrosion Resistance Corrosion resistant | Oxidation Resistance Readily reacts with oxygen | Reactivity Reactive to acids and alkalis | Magnetic Properties Non-magnetic | Flammability Non- flammable |

Alloy Type Bronze | Corrosion Resistance Corrosion resistant | Oxidation Resistance Readily reacts with oxygen | Reactivity Reactive to acids and alkalis | Magnetic Properties Non-magnetic | Flammability Non- flammable |

Alloy Type Aluminum Alloys | Corrosion Resistance Corrosion resistant | Oxidation Resistance Readily reacts with oxygen | Reactivity Reactive to acids and alkalis | Magnetic Properties Non-magnetic | Flammability Non- flammable |

Alloy Type Titanium Alloys | Corrosion Resistance Corrosion resistant | Oxidation Resistance Readily reacts with oxygen | Reactivity Reactive to acids and halogens | Magnetic Properties Non-magnetic | Flammability Flammable |

Alloy Type Nickel Alloys | Corrosion Resistance Corrosion resistant | Oxidation Resistance Readily reacts with oxygen | Reactivity Reactive to acids | Magnetic Properties Ferromagnetic | Flammability Non- flammable |

Alloy Type Copper-Nickel Alloys | Corrosion Resistance Corrosion resistant | Oxidation Resistance Readily reacts with oxygen | Reactivity Reactive to acids and alkali | Magnetic Properties Ferromagnetic | Flammability Non- flammable |

Table Credit: https://www.copper.org/

What Are the Applications of Alloys?

Alloys appear everywhere - any metal parts you encounter in your day, from a bicycle frame to a spoon, from a crane to a car, are made from alloys, as we rarely use pure metals. Some typical applications of the common alloy groups are:

1. Construction

We see Steel and Aluminum alloys used often in construction, exploiting their elevated strength and durability. The range of construction applications is extensive, from rebar (mild steel) to faucets (brass), from sidings (Aluminum) to beams (hot or cold rolled steel), from window frames (Aluminum) to handrails (stainless steel).

2. Transportation

We also see Aluminum alloys being heavily utilized in the entire transport sector. Airframes and skins/control surfaces (Aluminum), truck chassis (steel and Aluminum), monocoque car bodies (steel), fuel tanks (Aluminum or steel), engines (Cast Iron, Aluminum). They are typically high strength-to-weight ratio, are corrosion-resistant, and recyclable. Aluminums weight influences fuel efficiency by reducing overall vehicle weight while still fulfilling strength requirements, while steel is heavier but more fatigue-resistant.

3. Electronics

Alloys play a wide range of key roles in electrical components, offering tunable beneficial properties like high conductivity, high resistance, strength, and corrosion/electrochemical resistance. Cupro-Nickel and brass alloys are used in electrical wiring, switchgear, and connectors because of their superior electrical conductivity combined with mechanical durability. Nickel-chromium and Manganese alloys are used in resistors and heating elements, where precise electrical resistance and heat tolerance are required. The choice of alloys for electrical/electronic applications seeks performance, longevity, and operational efficiency. By tailoring the composition of these alloys, the desired balance of electrical and physical properties can be tuned, making various alloys key to modern electrical and electronic devices.

4. Medical Devices

Alloys are vital in medical devices, a major industry that Xometry services, delivering the required biocompatibility, strength, and corrosion resistance for implants, joint replacements, and stents, which must integrate well with and be tolerated by body tissues and fluids. Surgical instruments and dental devices are from various alloys, ensuring durability and precision. Typical metals/alloys tolerance of sterilization methods without degrading is central to their suitability for medical applications, patient safety, and device longevity.

5. Jewelry

Gold, Silver, Platinum, and other precious metals are used in jewelry. Despite their attractive properties, they are rarely used in pure form, as they are typically too soft to serve durably. Bronze, Cupro-Nickel, Nickel-Silver, and many more alloys are used to create lower cost jewelry. Alloying allows selection/control of the colors that can be obtained, which are not possible with pure metals.

6. Manufacturing

Alloys serve in all aspects of manufacturing, making both the machines/tools that perform the tasks, the buildings that house the machines, and the products that the machines make. Few areas of manufacture use pure metals - examples being chemical/catalytic processes and electrical conductors (typically high purity Copper or Aluminum).

Pipes made from alloy material

What Are the Benefits of Alloys?

You already experience the benefits of alloys over pure metals in every interaction with technology or the built environment. Here are some benefits of alloyed materials:

- Increased Strength: Alloys offer considerably higher strength than pure metals because of the intentional and tuned lattice disruptions that make it more difficult for atoms to migrate and crystal planes to slip over each other under applied load.

- Versatility: Alloying allows huge versatility, modifying the restaurant properties in highly tuned and application-specific ways that the native materials cannot compete with. Alloys are universally stronger and harder and selectively (but not always) more corrosion-resistant than the pure-primary constituent.

- Increased Hardness: Alloys are harder than pure metals due to the lattice disruptions that increase intra-granular strain, greatly altering the behavior.

- Corrosion Resistance: You are very familiar with some alloys that are highly corrosion-resistant. The coins in your pocket don’t corrode. The stainless steel of your watch-strap doesn’t either. Alloying elements like Zinc, Chromium, and Nickel readily react with oxygen but form an oxygen-excluding barrier layer on alloy surfaces.

- Cost Effective: Alloys can often be a means to both enhance properties AND reduce costs. Stainless steels cost more than mild steel, but require no surface protection and will have longer service life, reducing the net cost of ownership. Pure gold is both too soft and too costly to use. The addition of Copper hardens the material so it can be used as dental implants/fillings that cost much less while serving users better.

What Are the Limitations of Alloys?

The limitations of alloys compared to pure metals are listed below:

- Less Ductile: Alloys are typically less ductile than their pure metal constituents. While this can be a functional benefit in a finished part, it increases processing costs. Keep this in mind during the design process.

- Difficult to Weld: Alloys have lower melting points than their pure metal counterparts. This makes alloys harder to weld.

- Difficulty in Recycling: Alloys are more difficult to recycle than pure metals because alloys have many constituent materials.

- Can Be More Prone to Corrosion: While many alloys experience improved corrosion resistance over pure metals, this is not true for all alloys. Some are more susceptible to different forms of corrosion, such as galvanic or intergranular corrosion, which is less likely to occur with pure metals.

- Environmental Concerns: The production of some alloys can release hazardous and harmful fumes into the atmosphere. Creating alloys often requires more intense levels of energy, increasing their carbon footprint. This is one reason Xometry offers the option to offset carbon emissions on your project with our Xometry Go Green Initiative.

Frequently Asked Questions About Alloys

Are Alloys Rust-Proof?

Mostly yes. Alloys that do not contain iron will not rust, since rust is specifically iron oxide. However, alloys that do contain iron will eventually rust, except for stainless steel.

Are Alloys Hypoallergenic?

Mostly yes. Alloys that do not contain nickel, cobalt, and chromium (the metals that usually cause allergies) are hypoallergenic. If allergic, avoid using alloys with these metals.

Are Alloys Metals?

Yes, alloys are metals. They are good conductors of heat and electricity and have shiny surfaces.

What Is the Difference Between an Alloy and a Metal?

An alloy is a material consisting of base metal and additional elements. A “metal” is a classification for ductile materials, that have a lustrous appearance, and are excellent electrical and thermal conductors as compared to other classes of materials. All alloys are metals, but not all metals are alloys.

What Is the Difference Between an Alloy and Aluminum?

An alloy is a material composed of base metal and additional elements. Aluminum is a pure metal that is not combined with other elements. However, many aluminum alloys have been developed to have desirable properties that otherwise do not exist in pure aluminum.

Summary

This article presented alloys, explained what they are, and discussed the various types and their properties. At Xometry, we provide dozens of alloys to choose from to fit your specific prototyping and production needs across a wide range of manufacturing capabilities and other value-added services.

Choose from popular alloys like aluminum, steel, stainless steel, titanium, and more. You can explore all of our options by uploading your CAD files and get an instant quote today!

Disclaimer

The content appearing on this webpage is for informational purposes only. Xometry makes no representation or warranty of any kind, be it expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or validity of the information. Any performance parameters, geometric tolerances, specific design features, quality and types of materials, or processes should not be inferred to represent what will be delivered by third-party suppliers or manufacturers through Xometry’s network. Buyers seeking quotes for parts are responsible for defining the specific requirements for those parts. Please refer to our terms and conditions for more information.